2020-05-11

2018-11-30

Voltaire: filozofiaj rakontoj

- Zadig (1747/8)

- Micromégas (1752)

- L'Ingénu (La senartifikulo) (1767)

- Le Taureau blanc (La blanka virbovo) (1773/4)

Voltaire’s philosophical tales: commentary

En la artikolo pri Voltaire en Vikipedio konstateblas ke ekzistas tradukoj de pluraj verkoj en Esperanto. Rimarku ekzemple recenzon pri la jena:

Recenzo: Tri verkoj de Volter [Kandid, Zadig, Senartifikulo] (trad. E. Lanti) de Tomaŝ PUMPR (La nica literatura revuo, 3/3, p. 115-120)

Libroforme aperis ankaŭ:

- Mikromego kaj aliaj rakontoj [15 rakontoj], trad. André Cherpillod (Chapecó: Fonto, 2014)

- Katekismo de la honesta homo, trad. André Cherpillod (Chapecó: Fonto, 2012). Recenzas Renato Corsetti

- La franca jezuito kaj la ĉina imperiestro (Raporto pri la ekzilo de la jezuitoj el Ĉinio), trad. André Cherpillod (Courgenard: La Blanchetière, 2014)

- "Blanko kaj Nigro", trad. Roland Platteau

- "La unuokula ŝarĝoportisto", trad. Edgard Verheyden, en Flandra Esperantisto, okt. 1936, p. 53-57.

- "La unuokula ŝarĝisto", trad. Daniel Luez

- "La du konsolitaj", trad. René Bricard

- "Memnono, aŭ la homa saĝeco", trad. F. Lallemant

- Voltaire, 30 Majo 2017 (kun la recenzo de Tri verkoj fare de Pumpr)

- Voltaire, 21 Novembro 2018 (kun anekdoto "La ŝuoj de Voltaire")

Verkis

Ralph Dumain

je

3:28 PM

0

komentoj

![]()

Rubrikoj: ateismo, fabeloj, fikcio, filozofio, franca literaturo, Klerismo, kristanismo, liberpensado, mitologio, racio, religio, satiro, sciencfikcio, Voltaire

2018-04-14

On Carnap as an Esperantist & cosmopolitan (vs Heidegger)

This was the original “linguistic turn.” Recent biographies have strongly humanized Rudolf Carnap away from the image of a stern logician and into a true man of enlightenment and a utopian of international cooperation. Carnap favored the construction of “ideal languages” both in logic and in reality, artificial languages that could overcome the errors and historical demerits of natural language, not from any disapproval of human history but because he maintained the cosmopolitan Enlightenment ethos of Kant’s “Perpetual Peace,” as in his love of Esperanto. Friedman has pointed out the touching rhapsody in Carnap’s intellectual autobiography when he recounts teaching himself the language at the age of fourteen and attending a performance of Goethe’s noble Iphigenia performed in the rationalized international language. “It was a stirring and uplifting experience for me to hear this drama, inspired by the ideal of one humanity, expressed in the new medium which made it possible for thousands of spectators from many countries to understand it.” After the tragedy of World War I, young man Carnap hiked through Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania with a Bulgarian friend: “We stayed with hospitable Esperantists and made contact with many people in these countries. We talked about all kinds of problems in public and in personal life, always, of course, in Esperanto.”

SOURCE: Greif, Mark. The Age of the Crisis of Man: Thought and Fiction in America, 1933–1973 (Princeton University Press, 2015), chapter 10--Universal Philosophy and Antihumanist Theory, pp. 288-289.

Verkis

Ralph Dumain

je

11:55 AM

0

komentoj

![]()

Rubrikoj: Ernst Cassirer, faŝismo, filozofio, Goethe, Heidegger, interlingvistiko, Klerismo, kosmopolitismo, logiko, naziismo, racio, Rudolf Carnap, socialismo, teatro

2017-07-26

Sándor Szathmári on the monomania of prophets

Sándor Szathmári on the limitations of sages

But I found Szathmári's take on this so compelling, I finally wrote a comparable post on my Reason & Society blog:

Sándor Szathmári on the monomania of prophets

There I added a detail without explaining further: the boldfaced passage reminded me of an aspect of Hermann Hesse's Siddartha that irritated me when I read it as a teenager. Siddartha meets the Buddha, and objects that the Buddha is just babysitting his followers who have not experienced what the Buddha is preaching, the Buddha makes excuses for this, and Siddartha accepts this while moving on. So Hesse has it both ways. Hence Szathmári's commentary stood out for me. I repeat the key passage below. The translation is awkward, so I should re-translate it myself from the Esperanto:

"To be a bikru is also in fact a monomania; the erroneous belief that with the Behins there is a connection between the heard word and the brain. A bikru is a Behin whose only Behinity is that he doesn't realize among whom he lives; for it could not be imagined, could it, that somebody who was aware of the Behinic disease would still want to explain reality to them."

Verkis

Ralph Dumain

je

1:51 PM

0

komentoj

![]()

Rubrikoj: beletro, fikcio, filozofio, Hermann Hesse, hungara literaturo, kulturkritiko, literaturkritiko, pesimismo, racio, religio, saĝuloj, Sándor Szathmári, satiro, sciencfikcio, scienco, utopio

2017-07-12

Voyage to Kazohinia: A Diametric Dystopia (2)

As I pointed out in a recent post, what is today known as the diametric model of the mind and mental illness was stunningly anticipated by Sándor Szathmári (1897–1974) in his novel, Voyage to Kazohinia, first published in Hungarian in 1941. To the best of my knowledge, this is the earliest anticipation of the idea that autism and psychosis might be opposites—despite the author seemingly knowing nothing of autism or of the work of Hans Asperger, who was about to publish his first account of Autistichen Psychopathen im Kindesalter in wartime Austria.

Verkis

Ralph Dumain

je

10:30 PM

0

komentoj

![]()

Rubrikoj: Christopher Badcock, Jonathan Swift, kulturkritiko, medicino, psikologio, racio, recenzoj, Sándor Szathmári, satiro, sciencfikcio, utopio

Voyage to Kazohinia: A Diametric Dystopia

"The diametric model of mental illness was anticipated in a novel of 1941."

Badcock summarizes the schema of Szathmári's novel. He notes that Gulliver proves incapable of recognizing the similarity between his Britain and the irrational Behins. Later Badcock notes that the behins are tangled up by their own mental constructs, unable to engage objective reality.

"But by now many readers of these posts will already have noticed that to present-day eyes the Hins look very much as if they collectively suffer from high functioning autism spectrum disorder (ASD); while the Behins are afflicted with diametrically opposite psychotic spectrum disorder (PSD). This remarkable book, in other words, prefigured the diametric model of mental illness by a full fifty years. In Szathmári’s words, the Hin and Behin represented “Two worlds, which could never perceive each other simply because the other was not a separate entity but the reverse of itself…” Like mentalistic versus mechanistic cognition, these were “opposite worldviews,” the former the “positive” of the other “negative.”"Badcock finds the translation somewhat wanting, but also regrets that this "masterpiece" so relevant to psychological understanding and today's world has been overlooked.

"But its author deserves full credit, not only for writing one of the most brilliant satires of modern times, but also for implicitly understanding the diametrically opposite nature of autism and psychosis, mentalistic and mechanistic cognition—not to mention the threat to sanity and civilization of hyper-mentalism."Badcock was informed of this novel by one Simone Hickman. Perhaps it is possible to learn more about her?

This is a unique and remarkable tribute. I am not familiar with Badcock's work or the concepts he uses, but if he recognizes a psychological dualism here, he, or we in any case, should recognize that this mirrors an ideological and rock-bottom societal dualism patterned in the modern world.

Verkis

Ralph Dumain

je

8:45 PM

0

komentoj

![]()

Rubrikoj: Christopher Badcock, Jonathan Swift, kulturkritiko, medicino, psikologio, racio, recenzoj, Sándor Szathmári, satiro, sciencfikcio, utopio

2013-08-17

William Blake vs 17th-18th century linguistics (2)

Essick, Robert N. William

Blake and the Language of Adam. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989.

See previous post on this topic for table of contents, etc. And see my web site for:

- Introduction: on the state of scholarship on Blake as artist & as poet, & on previous studies of Blake's linguistic concepts, the focus of this book: Blake compared to the rationalist & empiricist linguistic ideas of the 17th & 18th centuries

- William Blake vs Rationalist Linguistics (Excerpt) from Chapter 3: Natural Signs and the Fall of Language; pp. 133-135.

Verkis

Ralph Dumain

je

10:33 AM

0

komentoj

![]()

Rubrikoj: filozofio, interlingvistiko, John Wilkins, lingvistiko, racio, Romantikismo, scienco, William Blake

2013-08-12

William Blake vs 17th-18th century linguistics

Verkis

Ralph Dumain

je

2:12 AM

0

komentoj

![]()

Rubrikoj: filozofio, interlingvistiko, John Wilkins, lingvistiko, racio, Romantikismo, scienco, William Blake

2013-03-22

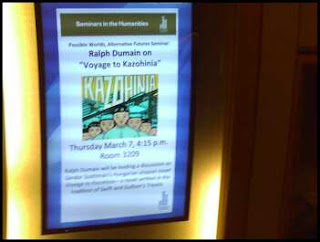

Ralph Dumain leads seminar on "Voyage to Kazohinia" at CUNY (2)

The seminar took place on 7 March 2013. I began with a ten-minute introduction, which I will convert into a publishable piece. The discussion that followed took up the balance of the two-hour seminar. The dozen attendees all contributed the most stimulating ideas. I have summarized a number of the most important of these ideas in a guest blog post:

Ralph Dumain Guest Blog Post: Reflections on Voyage to Kazohinia Seminar

Verkis

Ralph Dumain

je

3:07 PM

0

komentoj

![]()

Rubrikoj: beletro, fikcio, filozofio, fotografoj, Hungario, ideologio, kulturkritiko, literaturkritiko, pesimismo, prelegoj, racio, religio, Sándor Szathmári, satiro, sciencfikcio, scienco, utopio

2013-03-14

Ralph Dumain leads seminar on "Voyage to Kazohinia" at CUNY (1)

Above is the poster for my seminar.

Below are the various announcements on CUNY (City University of New York) blogs:

Ralph Dumain on "Voyage to Kazohinia"

CUNY Academic Commons: Possible Worlds, Alternative Futures: The Utopian Studies Seminar of CUNY

March 7: Seminar with Ralph Dumain on Voyage to KazohiniaThe Center for the Humanities:Possible Worlds, Alternative Futures: Utopianism in Theory and Practice

Some Resources in Preparation for Thursday’s seminar

Podcast by Ralph Dumain

Ralph Dumain on "Voyage to Kazohinia"Here is a quick snapshot of an electronic bulletin board (posted at various places in the building) advertising the event:

Here is a photograph taken at the seminar, courtesy of Neil Blonstein:

I began with a 10-minute introduction. A lively discussion followed, the attendees, consisting mostly of professors and graduate students, all of whom asked key questions and contributed important thoughts on the subject. The event was a smashing success. I will write up a full report.

Verkis

Ralph Dumain

je

7:59 PM

0

komentoj

![]()

Rubrikoj: beletro, bildoj, fikcio, filozofio, fotografoj, Hungario, kulturkritiko, literaturkritiko, pesimismo, prelegoj, racio, religio, saĝuloj, Sándor Szathmári, satiro, sciencfikcio, scienco, utopio

2013-03-07

Sándor Szathmári on the limitations of sages

I am presenting a priceless passage which I highlighted in my previous reading and in this one. The bikru are the rare prophets and sages among the Behins who are routinely martyred, deified, and whose wisdom is ignored or violated. But Zatamon finds a fatal flaw in them:

"The Behin' s brain doesn't separate self-radiation from the cosmic rays and that the receiver distorts in a complicated manner only confirms the fact of distortion. The more they know the more foolishly they will think; the hungrier they are the more food they will throw out; the less struggle required to produce our daily bread, the more they will kill each other for it; and when they writhe hungrily, sick and suffering they will hope to regain their strength through the "breath" of the mufruk, the kipu, the boeto, the yellow pebble or the salvation of the knife."

"There were also quite sensible Behins," I put in. "I heard of some bikru..."

"Yes, there are ones whose intellect understands the necessity of the kazo but their being is still Behin and this renders their way of thinking imperfect and prevents them from achieving full perception."

"What do you mean by that?"

"Their obsessions are characteristic of the Behins. The imagined misbeliefs."

"And what of the bikru?"

"Don't speak of 'the' bikru. You shouldn't think that they had only one bikru. There were several. Perhaps, you, too, might have become one of them."

"Indeed?!" I looked at him flabbergasted.

"Yes. They burn every bikru first. Later they recognize him because, as you yourself have seen, they have minds but the self-radiation doesn't allow them to dominate clearly and as soon as it comes to words, to say nothing of deeds, everything becomes reversed. The bikrus, however, have the ability to manifest their intelligence but, as I have said, in their being they are Behins and they are not free of imperfections and fixed ideas."

"Of fixed ideas? What is this fixed idea?"

"To be a bikru is also in fact a monomania; the erroneous belief that with the Behins there is a connection between the heard word and the brain. A bikru is a Behin whose only Behinity is that he doesn't realize among whom he lives; for it could not be imagined, could it, that somebody who was aware of the Behinic disease would still want to explain reality to them."

Verkis

Ralph Dumain

je

11:13 AM

0

komentoj

![]()

Rubrikoj: beletro, fikcio, filozofio, Hungario, kulturkritiko, literaturkritiko, pesimismo, racio, religio, saĝuloj, Sándor Szathmári, satiro, sciencfikcio, scienco, utopio

2013-02-21

Transhumanism in the 1930s: Szathmári, Bernal, Horkheimer

While reviewing and researching Sándor Szathmári's classic Voyage to Kazohinia last year, I revisited and recognized the importance of this article:

Schäfer, Wolf. "Stranded at the Crossroads of Dehumanization: John Desmond Bernal and Max Horkheimer," in On Max Horkheimer: New Perspectives, edited by Seyla Benhabib, Wolfgang Bonß, and John McCole (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993) pp. 153-183.

Here is what I wrote on 28 December 2005 upon first reading this essay:

This is right in keeping with a major concern: i.e. the incapacity of the Frankfurt School to engage intelligently the natural sciences, an inadequacy yet to be repaired. Schafer is pointed in his diagnosis of how the split between the "two cultures" (anyone still remember C.P. Snow?) could not be more sharply manifested than in the fundamental orientation of these two individuals.Returning to this essay last year, I was not so interested in Horkheimer's shortcomings as I was in Bernal's and in a key contraposition in 20th-century intellectual history that the Horkheimer-Bernal juxtaposition exemplifies.

What is essential to understand here is not only an absolute antithesis between Bernal and Horkheimer II, but the fact that both were products of two cultures--science and humanistic--that did not intersect or understand one another. (170-1)

Schafer quotes Horkheimer's The Eclipse of Reason (p. 75) to point up his hopeless position:

"that the division of all human truth into science and humanities is itself a social product that was hypostatized by the organization of the universities and ultimately by some philosophical schools, particularly those of Rickert and Max Weber. The so-called practical world has no place for truth, and therefore splits it to conform it to its own image: the physical sciences are endowed with so-called objectivity, but emptied of human content; the humanities preserve the human content, but only as ideology, at the expense of truth."Schafer's evaluation of Horkheimer's position is not kind:

"If one could regard this statement itself as true and as not being warped by ideology, then the professional fractalization of truth could be cured and made whole and healthy again by a new social product, perhaps by reorganizing the universities and our intellectual life according to the gospel of some holistic philosophical school. False objectivity and true ideology could be overcome; truths without human content could be rehumanized; and truths with untruthful human content could be corrected. But the view of Horkheimer II cannot be true since it was produced inside the humanities--those branches of learning that preserve the human content . . . as ideology." Horkheimer must situate his own thinking in this ideological context. We may as well conclude, therefore, that Horkheimer II fell victim to his own deconstruction of occidental reason--that he is part of the problem and not of the solution." [172-3]Schafer also criticizes Bernal, but then he returns to the shortcomings of critical theory:

"But neither early, middle, nor current critical theory has paid, or is paying, enough attention to the sciences and technologies that feed into and shape the natural half of human history. The dreams, fantasies, and projects of our technoscientific culture thrive with very little or no internal technocritique that is not purely technical; our most eloquent technocritics are often crudely antitechnological; and relevant academic fields, like the professional history and sociology of science and technology, care more about their own problems and research fronts than about society at the crossroads into the future." [173]I would have phrased this differently. The key here is the incompetence of the humanistic critics of science and technology, not their willingness to criticize.

Schafer concludes with what the universities might and could do to bridge the divide, but specialization is so firmly entrenched there are no signs of any remediation.

So in the end this essay is a cry of alarm about the "two cultures", rather than the specific shortcomings of Horkheimer's philosophical understanding of the natural sciences. But as far as he goes, I'm in near complete agreement.

Though Horkheimer was on the warpath against positivism, as were his philosophical colleagues, it should be noted that the logical positivists that had recently come into prominence were on the left. Bernal, a scientist and eventually a pioneer historiographer of science, himself became a Communist, I don't know when offhand. In question here is Bernal's 1929 work The World, the Flesh, and the Devil, in which Bernal projects the transcendence of human physical existence, presenting a transhumanist vision which can readily be classified as a precursor of Szathmári's 1964 novella Maŝinmondo (Machine World).

For an extensive overview of this theme, see: Christopher Coenen, "Utopian Aspects of the Debate on Converging Technologies"; Pre-Print: 13.11.2007.

One man's utopia is another man's dystopia. The basic themes of transhumanism, while still being debated, are old now, but there was a time when they were fresh, spanning a half-century from Wells to Orwell. Szathmári merits induction into the utopian/dystopian/transhumanist Hall of Fame as one of its central figures.

In the critical literature on Szathmári in Esperanto there are some incisive critiques of the philosophical assumptions underlying Kazohinia. While there exists in Esperanto a bit of material and references here and there to the philosophers of the Frankfurt School and related thinkers, no one has yet staged a confrontation of Critical Theory and Szathmári's work. The Frankfurt theorists drew on the irrationalist philosophical heritage but always with the goal of preserving Reason, which they saw as degraded by positivism. There are still lessons to be learned from the warring dichotomies of the past century.

Verkis

Ralph Dumain

je

8:03 PM

0

komentoj

![]()

Rubrikoj: beletro, fikcio, filozofio, Frankfurta Skolo, Hungario, J. D. Bernal, kritika teorio, kulturkritiko, literaturkritiko, Max Horkheimer, pesimismo, racio, Sándor Szathmári, satiro, sciencfikcio, scienco, utopio

2013-02-20

Symposium on Sándor Szathmári: videos revisited (3)

As the 6 June 2012 book launch of Voyage to Kazohinia at the Hungarian Consulate in New York begins, publisher and M.C. Paul Olchvary introduces me, and my introduction to Szathmári's life and ideas follow:

Ralph Dumain discusses the classic novel Voyage to Kazohinia

I mention Szathmári's investment in Esperanto as an expression of idealism in contradiction to his philosophical pessimism. His major influences were Jonathan Swift, Imre Madách, and Frigyes Karinthy. His trilogy In Vain (in Hungarian only), briefly outlined here, was abandoned and was published only posthumously. The checkered publishing history of Kazohinia punctuated by periods of political repression, is outlined. I summarize Szathmári's ideas expressed in his essays and interviews and the themes of his other fiction (all published in Esperanto), emphasizing Maŝinmondo (Machine World) as the logical conclusion of the rationalism expressed in Kazohinia.

Discussing Voyage to Kazohinia--June 6 book launch

In this segment Edie Maidav mentions Huxley's Brave New World and follows emphasizing the bifurcated u/dystopian structure of Szathmári's novel. She poses the question: why this original two-part structure? Gregory Moynahan responds that Swift also works with unresolved dichotomies. The example of the Hin and Behin approaches to sexuality is given.

I suggest that understanding is best achieved by taking things to extremes, in contradistinction to the muddy way we encounter tendencies in everyday life. I was engaged with these fundamental (utopian and extreme) questions as a teenager. In Kazohinia we find a triangulation of these extremes with Gulliver, and a further triangulation involving us as readers, who presumably see beyond Gulliver's clichéd view of the world. Key also are the successive iterations of the ability to see through the foibles of others coupled with the inability to see the same flaws in oneself. Consider the extreme rationalism combined with extreme literalism of the Hins contrasted with Behin society in which words never conform to reality, with an extremity that beats even the irrationality of human society. Analyzing these extremes is an exciting prospect.

Szathmári himself never said there was anything wrong with Hin society. Several of the reviewers and critics (all in Esperanto) could not believe that Szathmári meant what he said. Some have been able to accept the notion that Szathmári's pessimism concords with the notion that Hin society gives us an unattainable standard of perfection against which to measure ourselves.

Szathmári was brilliant in presenting this dichotomy (very present in the 1930s), and we can benefit by taking Greg's remarks about the philosophy of science into account while revisiting this dichotomy as we ought to do.

Paul takes the microphone and recounts his discussion with an old Hungarian who took Szathmári as a socialist; other Hungarians also see Szathmári as a pessimistic socialist who sees socialism as an unattainable utopian ideal.

Verkis

Ralph Dumain

je

12:06 PM

0

komentoj

![]()

Rubrikoj: beletro, fikcio, filozofio, Hungario, kulturkritiko, literaturkritiko, pesimismo, racio, Sándor Szathmári, satiro, sciencfikcio, scienco, utopio, videoj

Symposium on Sándor Szathmári: videos revisited (2)

The 6 June 2012 book launch of Voyage to Kazohinia included a staged reading, introduced and narrated by publisher and MC Paul Olchvary:

`

As the YouTube description puts it: "Actors Adam Boncz and Andrea Sooch read an adaptation from Sándor Szathmári's masterpiece--from chapter 7, in which Gulliver makes the mistake of falling in love with a lovely but emotionless Zolema." And here is part 2:

Aside from Gulliver's conventional and unrealistic notions about romance, the need for a human connection is powerfully expressed. In the 1930s, Zolema's unadorned desire for sex would have been provocative. Note, however, that the impersonal, strictly utilitarian ethic of mechanical efficiency contradicts the motive of a purely pleasurable reaction to natural, physical stimuli which would naturally be embodied in an organic being. For its time this was still a novel scenario. It is a rationalism that is now easily recognizable, but hopefully also readily recognizable as pseudo-rationalism. This scenario can also be seen as positivism translated into the totality of human life, which few positivists who actually lived would have wanted to see taken to such a conclusion.

Verkis

Ralph Dumain

je

9:51 AM

0

komentoj

![]()

Rubrikoj: amo, beletro, fikcio, filozofio, Hungario, kulturkritiko, literaturkritiko, racio, Sándor Szathmári, satiro, sciencfikcio, sekso, utopio, videoj

.jpg)